The professors and graduates of Polotsk Jesuit College and Polotsk Jesuit Academy “discovered” America two centuries ago. For example, Giovanni Grassi became the President of Georgetown University and Francis Dzierozynski headed the entire system of the Jesuit educational establishments in the USA.

Nowadays, the lecturers and students at Polotsk State University have the opportunity to study the language, history and culture of the great transoceanic country and communicate with Americans staying at their home university. However, it is not because of modern mass media and information technologies. It’s because the lecturers from the United States have been regularly coming to our university since 2015 thanks to the Fulbright Program.

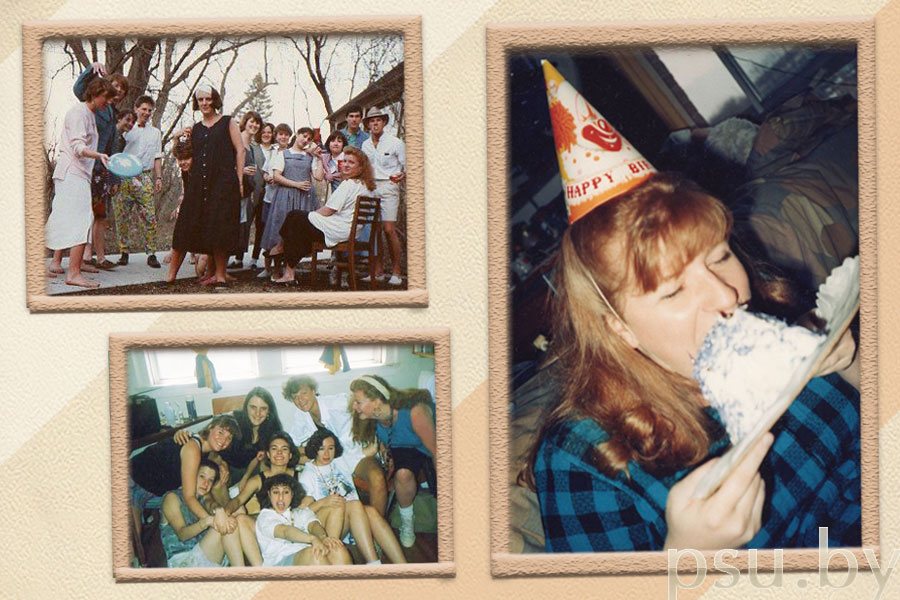

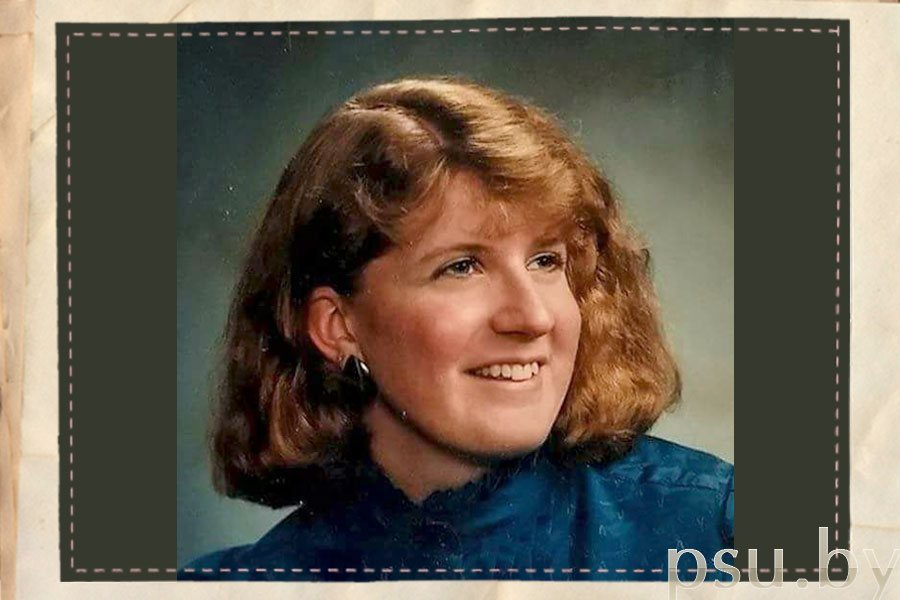

The current semester is not an exception. We have already written about Jocelyn Pihlaja, an American lecturer of the English Language and Literature at Lake Superior College (Duluth, Montana). Now it’s high time to get to know her better!

Corr.: Ms. Pihlaja, would you tell us about your school and college years?

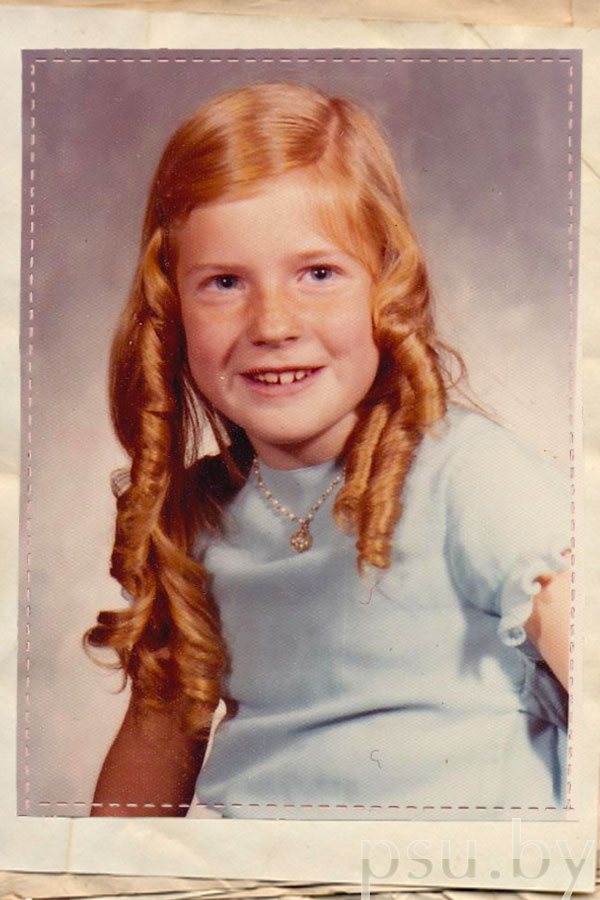

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I was born in a state called Montana. It is a state of agriculture and cowboys. Montana is known as Big Sky Country. This is because when you are in Montana, the sky seems to be bigger. It is amazing, and it is a very beautiful state.

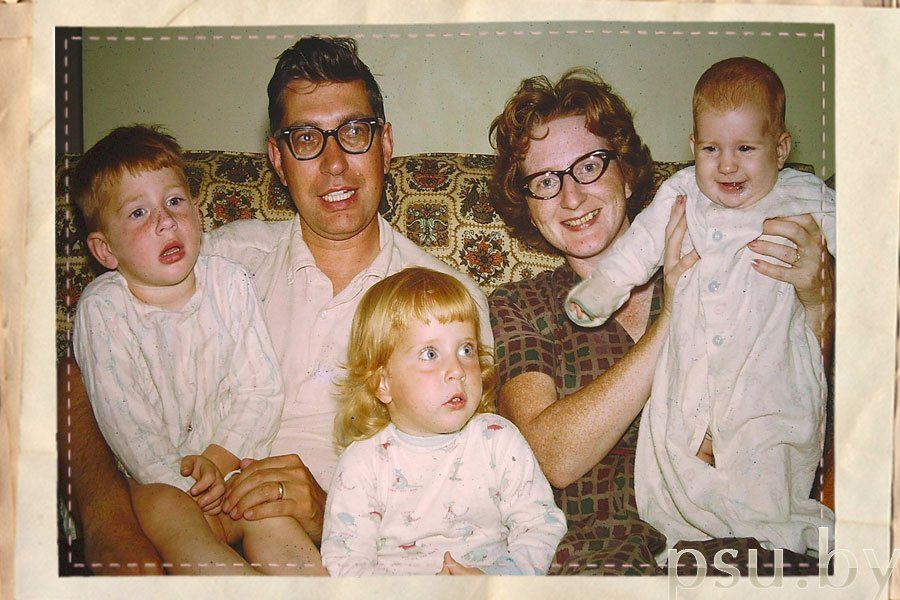

My family was unusual. We lived in this state with not very many people but a lot of wide-open spaces. But my father was a voice professor and opera singer. He was a very refined man. My mother was the executive director of the symphony in our town. She was not a maestro, not a conductor, but she was the business manager. My father was always giving voice lessons. Every night my mother would be making dinner, and somewhere in the house was “La-la-la-la-la!” So my brother, my sister, and I – we were three kids – always grew up with voices singing around us. My mother was an English major and music minor, and so we had many books in our house. The highest values were, “You should read, and you should love music!”

Corr.: What a lovely childhood!

Jocelyn Pihlaja: And that’s not all. My father had a choir at the college, and every five years he would take his students on the tour of Europe. My mother would always go on this tour as well. My parents would leave us maybe with our grandparents or sometimes with neighbors, so they could travel.

I grew up seeing this feeling of adventure and exploring other cultures. I could see how my parents were willing to nourish it. They would go to the bank and would take out a loan if they didn’t have enough money, so they could afford this travel. And my father would take maybe thirty students with him, and they would sing in cathedrals or different community spaces around Europe: in Paris, in Austria... So these were our household values that I grew up with. And it was always an expectation that all of us would go college.

When I was a senior in high school, it was at the point in the five-year rotation when my father was taking his choir to Europe. That year it was a celebration of Bach’s Tricentennial. My mother was going. My sister also decided: “I will go on this trip.” My brother was at the university, and he couldn’t go. And I thought: “I want to go, too!”

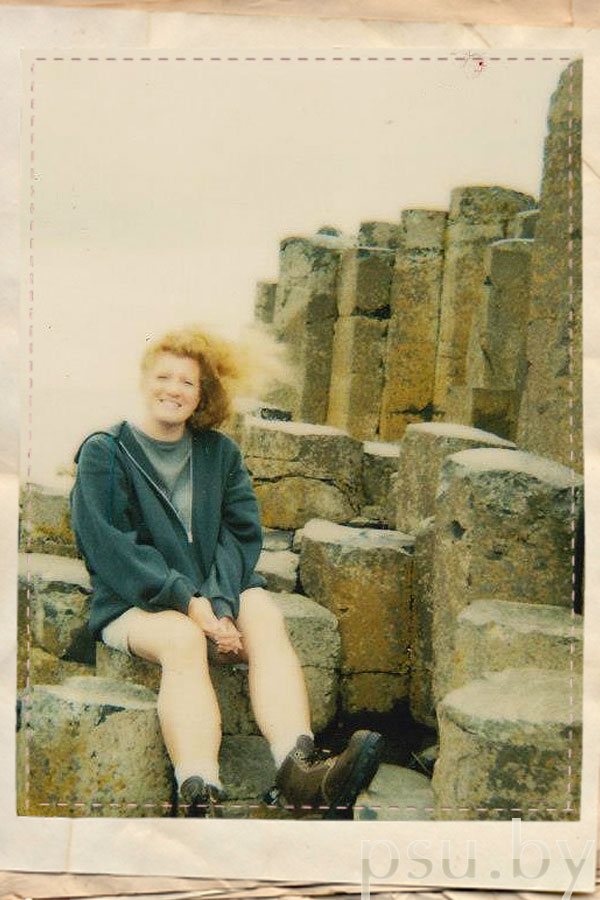

It was 1985, and the tour would go through something like eleven countries. There was the Soviet Union still, and we went to Czechoslovakia and through Eastern Germany. We went to Checkpoint Charlie, the famous Berlin Wall crossing point between East Berlin and West Berlin during the Cold War. So I was able to have Eastern/Soviet experience before the end of the USSR.

The trip was very good. But to take this tour, which was three weeks long, I would miss a big chunk of the end of the academic year. And it was the end of high school for me! Even worse, my school had an attendance policy: if you missed too many days, you wouldn’t graduate. I had missed three days already. I was the president of AFS, the American Field Service, which was a student club focused on travel (a year before, I had gone to Denmark and lived with a family through AFS). So one day I missed some classes because I was setting up something – I was at the school, but I was in the auditorium and not the classroom. Another day I was with the National Honor Society, a nationwide organization for good high-school students. One day, we were taken from the school to see some things, so I was counted absent.

Thus, I had these absences, and then I said: “I would like to go for twenty days with my father’s choir on a tour.” And the school said: “You can only miss twenty days or you don’t graduate. If you go, you cannot graduate.” My parents petitioned the school board: “Please! Special circumstances…” And the school-board said: “No.”

At this point, I had already been accepted to the college that I wanted to go to. We contacted the college and said: “Hypothetically, if I did not graduate from high school, could I still come to you with no high-school diploma?” And they said: “Yes! If you were doing this trip to Europe at our college, we would give you credit for this trip. We would not penalize you. We would say: ‘Yes, do this! This is amazing!’” So I knew I had chosen the right college! After that, I dropped out of high school. I just stopped going.

Corr.: This is an incredible story for our country!

Jocelyn Pihlaja: It is a pretty incredible story for the United States, too. Usually in the USA if someone does not finish high school, it means that a girl is pregnant or he or she is a drug addict or has some other problem. My problem was that I wanted big things.

So I went on this tour to Europe with my father’s choir. And it was amazing! I am still glad that I did that. Anyhow this shows you who my parents were, what was important to our life. I still do not have a high school degree. I am 51 years old, and it does not matter now.

Corr.: What college did you go?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I went to Carleton College in a small bucolic town with cornfields and cows. It is in Minnesota where I live now. From Montana in a car it is like a 16-hour drive, and it is a thousand miles away. It is a really good small private liberal arts college. There are only non-technical majors: Political Science, Psychology, and those kinds of things.

I went to college thinking that I would major in Political Science. And then I would go to law school, and I would become a lawyer. I took my first Political Science class, and I thought: “I hate this. I’m not interested in this. I don’t understand why we are talking about this.” I immediately asked myself: “What do I love? I love to read; I love to write. This is my whole life.”

I became an English major, and my concentration – some colleges call it a “minor” – was Film Studies. So I took many literature classes, many film classes, and then I graduated with my bachelor’s degree in English literature.

Corr.: What classes did you like most?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I had to take many classes where I did not really like what we had to read. I had to take, I think, two semesters of early English Literature with Beowulf and this kind of stuff. It was boring. I do not like this kind of reading. And then the next semester was a course that covered topics like the Romantic Poets. It was a little better, but still it felt like work. Then I took a class in 18th century novel. It was interesting to me to see the birth of the novel because I love novels. This class was interesting for it gave me a historical foundation for the things that I love now.

One class that I really loved was Western Literature – and by that we do not mean the Western hemisphere but the western part of the United States. Because there is a certain kind of author in the western part of the Unites States and because I grew up in the West, I have a resonance with this kind of thing. That class was very important to me also because the professor was so passionate about this subject. He was a very good storyteller. Wayne Carver was his name. You never knew what each class period would hold. Maybe we were supposed to talk about a certain novel, but he would come in a room, and he would start talking, telling stories from his life. But it was OK because it was so interesting! It was beautiful to witness this, to witness someone so comfortable in front of the classroom. For me that was just as much education as reading the books.

Corr.: How did you decide to be a college teacher?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: It’s very funny because I am now in my twenty-eighth year of teaching, and I never really wanted to be a teacher. I realized at some point that I needed be able to earn an income and make a living. I finished my bachelor’s degree in English Literature, and then I took two years where I just was a free spirit. One year I lived in Minneapolis, which is a big city in Minnesota, and I worked as a nanny – I took care of children. I also did what we call temp jobs, temporary work – I “temped.” I worked for corporations and filed papers.

The next year I thought, “I want to see more of the country.” So I just drove around the States; anywhere I knew somebody I went and visited. I thought things like, “I should see where Elvis Presley lived. I better go to Memphis, Tennessee. I better go to Graceland.” I just drove and went there. Then I thought, “I have a friend in Texas…” So I just drove around and camped. I only needed gas money and maybe some food. But when I went from friend to friend, to friend, to friend, they could feed me. I could say, “I’m hungry, and I need a bed.”

At one point, I thought, “I’ve never been to Mardi Gras and should go to New Orleans!” When that idea occurred to me, I was in Montana at my parents’ house, and I had friends in Colorado. And I said, “I’ll just drive ten hours to Boulder, Colorado, and pick up three friends.” Then we drove 24 hours to New Orleans and did Mardi Gras, which is a huge party where everybody is drunk on the streets 24 hours a day.

It’s funny, but my biggest remembrance about going to Mardi Gras is about coffee. I had never drunk coffee although I was 24 years old. I remember we arrived at New Orleans at 6 o’clock in the morning, and we were like, “Let’s party!” At the same time, I thought, “I’m so tired…” So I had my first cup of coffee. I needed some caffeine before I could party at Mardi Gras.

Corr.: And then at some point you decided to be a teacher, didn’t you?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Yes, I did! During these two years of playing, I had a growing awareness that I would need to become an adult. I had a lot of student debt. In the U.S., we take out loans to pay for education, and I needed to start paying these fees back. If you love travel – and I knew I really did – you have to have money. So I thought, “For the life I want, I need to figure out how to get a career and be a serious person.”

Considering my options, I thought, “Well, if I get a master’s degree in English Literature, how could I take my English degree and turn it into something practical that I can use for a career and use in a way that I could travel? I would need to also get a PhD before I could use that degree.”

Eventually, I decided to pursue a program in teaching English as a Second Language, ESL. I went to University of Idaho and got a master’s degree in ESL. In the United States, a master’s degree is the terminal degree for English as a Second Language. This program was two years, and it was half linguistics and half teaching methodology. The way the university helped me pay for this education was they gave me an assistantship, and I started teaching. In addition to my graduate studies, I would teach, in the fall, two sections of writing and in the spring one section of writing. At this university, they always had one section of writing that was all ESL students. In such a class, nobody was a native English speaker, but they were from everywhere – Sweden, Ghana, Vietnam, etc.

Corr.: And you liked it and stayed in the profession.

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Yes! My career really has been teaching English Composition, a sort of academic writing. When I finished my master’s degree after two years, the only practical experience I had was in teaching Comp.

At that point, my next decision about teaching came about because I was in a relationship with a guy who lived in Colorado, and I wanted to be closer to him. I applied to every college and university in Colorado, and I got a job teaching full time Comp at the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs.

I moved there and lived there for three years. This was when I really realized again, “When you have an English major, it’s very difficult to earn enough money to live on.” I was making not enough money, and also I had no health insurance. If anything happened to me, I would be bankrupt. After three years, I thought, “Now I’m a professional, but I’m not getting closer to having enough income to make choices: I don’t have enough money to buy a house; I don’t have money to take a trip. So what can I do?”

And then I looked at Minnesota where I had gone to college, and there I had family, and I had friends, and above all there is a very strong community college system. As you may know, community colleges are two-year colleges providing lower-level tertiary (continuing) education, granting certificates, diplomas, and associate’s degrees. So I applied all over Minnesota at all the community colleges. I took the first job that was offered to me. So I moved to Minnesota, and the guy from Colorado moved with me. Eventually we broke up. It was not a happy ending for the two of us, but in the bigger picture it was all for the best!

Corr.: Was the community college system what you were looking for?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Yes. I started teaching English and Literature in the community college system. Most of the teachers in the community colleges have master’s degrees, not PhDs. I really had realized that I didn’t want to get a PhD because I didn’t have an area of focused passion. And without that, why would I spend so much money and so many years? What I liked was being in the classroom with the students. And if you have a PhD, sometimes you do not teach very much – you just do your research. Although I hadn’t realized that I wanted to be a teacher, obviously, unconsciously I did. I wanted this job where I could be in this room with young people.

Actually, in community colleges, it’s not always young people. We have such a diverse student population at the community college. My oldest student was 88 years old! He walked in, and I thought, “Oh, Grandpa! Are you lost?” I said to him, “Are you looking for something? Can I help you?” But he had his pencil and his paper. He said, “No, I’m a student!” I was like, “Have a seat!” – “OK!” It was so incredible to have him in a writing class.

You know, in a writing class, sometimes you have 16-year-olds. You say, “Please, write something.” But they have nothing to share, unlike this old man. I had to stop him sometimes because he had so much to say! This is a joy, a wonderful thing about community college teaching. And we do truly get students as young as 16. There is a program where very good high school students can come to the college.

Also, we have a lot of online education. In last 10 to 15 years, I have often taught entirely online and never see the students face to face. The entire class takes place on the computer. Everything is submitted to me through the computer. All the communication is through the computer. Online education can either be very bad or very good. I have worked to make it very good, as much as possible.

In the community college system when I started teaching in Minnesota, I received a 100% pay raise over the University of Colorado. My salary doubled in the first year! And since then it has more than doubled again. So the community college is a really good way to be an English teacher. Looking at my salary and comparing with some of my friends who are lawyers and who are in other professions, it is OK!

Corr.: What courses do you teach now?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Now at my community college, I mostly teach writing, and I usually have one or two sections of literature each year. By a “section,” I mean a class which lasts 16 weeks, or one semester. Fall semester starts at the end of August and will go until almost Christmas. When a class meets on campus, students need 150 minutes – two and a half hours – per week. Some of them meet Monday, Wednesday, Friday for 50 minutes; some of them meet Tuesday and Thursday for 75 minutes; and some of them meet, for example, on a Tuesday night for 150 minutes. The way our schedules look is a result of a negotiation, where we submit our hoped-for schedule but are happy to teach when and how it is most needed. Our schedule is flexible. But in general, at my college, instructors teach five sections 150 minutes per week each. But if I teach online, I do not go at all to the college. If I have five classes online, sometimes I never go to campus except for meetings for committee work that I might be doing. But sometimes I have two online and three on campus classes. It is different every semester.

Corr.: What is your favorite course?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: One course that I would mention is the class that I developed for the curriculum probably five years ago. I was looking at what our English Department offers, and the problem always is that all of the courses seem abstract to the students. The writing courses are always about academic writing. So who is your audience for that? Your professor, maybe your classmates, some faceless people. It is not real-world writing!

And so I thought, “The main thing about modern students is this: they are writing all the time. They are! They are writing on Facebook, on Instagram. They are writing texts to each other. They are writing all day long! They are not just writing essays.” I thought a Social Media course, Writing for Social Media, could be done very well. If you have good online web presence, it can be powerful. And more and more companies are hiring social media writers to handle their various social media accounts. Nike needs someone to do their Facebook promotions and this kind of stuff. Twitter – companies need someone to write tweets. So you can have a good income as a social media writer.

I decided to see if I could develop this curriculum. There is a process, of course, at the college. You have to take your curriculum to this committee and to this committee, papers, papers…

Corr.: Is it easy to get such a course through all administrative bodies?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: It is not difficult. Everything took me two or three months. But it is simply because sometimes I was waiting for a signature. First, I had to talk to the English Department and my colleagues and say, “I’m thinking of developing this class. Could you support this? It would be a class where our students are doing real-world writing for real audiences. And they would genuinely be published where the whole world can see it.” Second, I had to demonstrate that there was a need for this kind of class, and I had to find something like comparable courses in the state. I looked at what other colleges and universities were offering, and nobody had it. There was only one Communication class. It was based around social media messages. I used this as an example. And then I had to make the case that our college could be leaders.

Among other things, this course became possible because my dean supported it. She had been in the English Department before she became an administrator. I think she understood that the problem with our students, why they are not motivated, is because, once again, of invisible audience. She said, “It will be very good for them to be writing to know that the world is going to see what they do. Then they might care about it.” This is true. If we post things for the world to see, we want them to be good.

Corr: Was it a success?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I have taught this course four or five times now. Usually it is an online course, and in most cases online courses are self-contained. We do it through the college system on the college’s learning platform. But with this Social Media course, we have a class Twitter account; we have a class Facebook account; we have class Instagram account! I make them have blogs, so they write blog posts. This means every week when I am grading, I am counting tweets. It is like 25 students and each have to tweet 4 times! It is so difficult logistically. It is a lot of work. But I feel like there is such a different energy to this class compared to everything else I have done for all these years.

When I teach this class, the first half of it we do from the personal perspective. On their blogs, they have to write about travelling they have done or some topic like this. Then, in the second half of the semester, we shift, and I make them choose either a real or an imagined organization. It can be a non-profit organization or whatever, but it has to be something that they will represent as a social media writer.

I had one student a few years ago. She was a Muslim woman, and she would only work from home. She said, “I would like to start my own business making cake pops. I’m not really ready yet to start this business, but I would like to learn. So one day if I do this, I will be ready because I have practiced writing promotional things for my cake pop business.” So she did that for the last 8 weeks. She made tweets, updates for Facebook, and blog posts, all of which were focused on coming up with ideas on how to make her business into a good presence online.

Many students choose an organization that does exist, something that they feel something for, like the Humane Society where you rescue pets. So they write about rescuing animals. One student said, “I actually want to start my own YouTube channel, but I want to start it as a money-making business.” For the last half of the semester, he was making videos for YouTube, but then he was promoting his channel through the other social media platforms.

We really talk about the power of cross-promotion, too. It is not enough just to post something once on Facebook. You need to post here and then there and then on another site. I do think a young person with mojo, a positive go’n get’em energy, and with an entrepreneurial spirit could go to some big company and say, “You don’t know it, but you need me as a social media writer. I can help you make more money because I can give you presence and engage potential customers!”

I had a student in this class few years ago. She was a mother. She was about my age in her mid-forties and had five kids. She gave birth to four quadruplets, and then a year later she had another baby! Anyhow, this was a woman I wanted as a student because, you know, she can handle herself. She took the Writing for Social Media class. She messaged me after few weeks, and she said, “I need to do some kind of service for my martial arts community before I test for my black belt. I was talking about our class with the teacher, and he asked me if I could do some social media writing for his dojo. What should I tell him I will do?”

And I said, “Well, first of all, this man has his small business by himself, so he probably really needs your skills. You should make sure that you are fair to him and fair to yourself too. How much time does he want from you?” And she replied, “Well, a few hours.” And I said, “Could you also barter with him? Tell him that you will handle his social media for him if it satisfies this service requirement. Tell him what you could do in return for this. Ask him what he wants and how frequently he wants you to post.” After some discussion, they came to terms, and that made me very happy; then this same student then began to handle the social media accounts for her kids’ high school and, more recently, for a new hostel that has opened in our city. Her practical use of social media writing skills made my heart sing. Overall, this class is something that I love, yet I dread it at the same time because it is so much logistical work.

Corr.: The Internet says you do some creative writing.

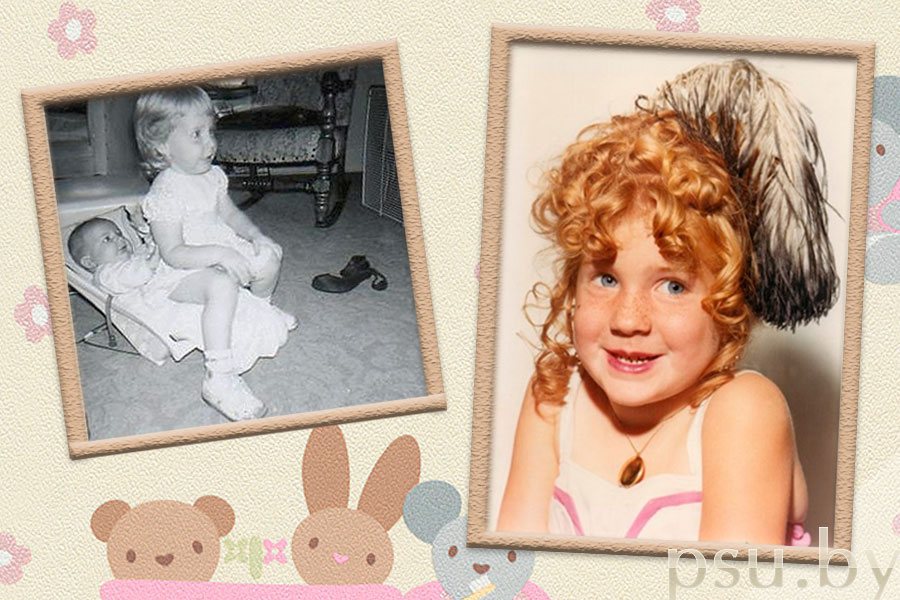

Jocelyn Pihlaja: In all things, I like to do it my way. I always wrote, even as a kid. I always wanted to be an author. I still have in my basement, in a box, my first “novel.” I wrote it when I was 10 years old. I even cut out pictures from magazines of all my characters. But as the years went by, I started to think maybe I wasn’t a writer because when I read interviews with fiction writers, they always said, “I have these characters in my head. I hear their voices.” And I thought, “I don’t hear any voices! I don’t feel like I’m a fiction writer.”

What I did know is that I really like telling stories. So I decided to explore non-fiction writing. And then I started teaching, got married, and had kids. During that time, I would just write good letters to the family. My Christmas letter was something that people really wanted to read because I poured myself into that Christmas letter.

My first child was born in 2000, and my second child was born in 2003. And then I was sort of recovering from motherhood. In 2006, I started a blog, and I still have it. So it has been 12 years now. And I have probably 600 hundred posts on this blog. I would get a lot of traffic to the blog, and I got some loyal readers. Eventually, some of these readers would message me and say, “I think you should submit some of your essays to some publications.”

Corr.: What kinds of essays did you share?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: There was a story of my daughter. She is now 18. When I was pregnant with her, I had a miscarriage. We did not know it was twins. I lost one embryo, but my daughter hung in there. I did not even know this was possible! All I knew was that a bad thing happened: I was in the hospital, I had a miscarriage, they pulled out tissue, and my pregnancy was over. Then we went back five days later. They were doing a scan, and they said, “There’s a heartbeat.” And I said, “No, no, no! I had… they took tissue out…” And they were like, “No, there’s a heartbeat.” So my daughter is an amazing miracle baby. I wrote this story on my blog, and people suggested, “You need to publish these kinds of stories in other places!”

Six or maybe seven years ago, I started submitting some essays to some online publications. I am not necessarily an artistic writer and not a commercial one, either. What I do is very much memoir. It is little slices of my life, stories, and observations. So I got things got published in a few different places. Sometimes it was a parenting type of magazine. I had one story in a parenting for teens magazine where I wrote about how my best parenting of a teenager happened.

The computer in our house was in our bedroom. Each day, my daughter would have her allowed time on the computer. And I always made sure that I was in that room folding laundry during her computer time. She was 14. If I asked her a question, she was, to put it mildly, unwilling to communicate. It didn’t work to just ask her a question because there was no answer. But when I was just next to her, all of a sudden, she would start a conversation, “Mom! You know what I’m really thinking…” And I was still folding laundry. Then she would be quiet for a few minutes and again, “Oh, listen, Mom. You’re gonna love this song!” And she would play it to me. So I realized that I had to pretend that my teenager was a cat. You have to ignore the cat, and then the cat wants to be on your lap. It was this kind of essay.

This is writing I did for a lot of years. Then a few years ago, I decided to try to get better at writing to challenge myself and, thus, try to submit my essay to literary journals. I wrote a couple of essays.

I wrote about my family. My mother divorced my father at almost forty years of marriage. They were about to hit forty years, and she divorced him. It is a terrible life story because my mother was always one of my best friends and, to be honest, now I struggle. I do best at loving her for being a good mother when I was younger.

So she was 67 years old when she divorced my dad. He was 67, too, and he died 5 months later… She did not tell him she was divorcing him. There was a knock on the door. A strange man was there who gave him papers. That is how my father learned that my mother was divorcing him. My mother stayed that night at her girlfriend’s house. And the next morning she got up at 6 o’clock in the morning and she went and got a nose job. 67 years old!

In response to her decision, I had to think, “Who is this woman?” I was 35 years old, and my brother, sister, and I were grown adults, but it was sort of like we did not know this woman anymore. She had always been a dominant person in my life but then… It was so painful, and it was so awful. It has been fifteen years now, but it still hurts. And all this falling apart with my parents occurred as I was having babies myself. I was becoming a mother and was losing my mother simultaneously.

She is 83, and she is in California now. She dated something like eight men in seven years. Then she married a guy a few years ago. He now has a kind of dementia. He just sits in his chair all day long reading the same magazine because he cannot remember it.

So I decided to write about some painful things. I submitted this essay to some contests. It did all right. It did not win, but it came in second place. I got some money for that. They published it. But a year later, I found out that they submitted it to another place, and it was included in an anthology. From that, I received the opportunity for a writer’s residency in Tennessee, which I did in the spring of 2018. There is a continued momentum to this one big essay.

Corr.: So your stories are more about your family experience, aren’t they?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Not necessarily. At this big teachers’ conference in Minsk this weekend, I am going to read another creative non-fiction essay of mine. This one I wrote after twenty-five years of teaching, and it was originally titled “Twenty-Five.” It was just a vignette of one student from each year of my teaching life – one student who affected me, who is important to me, who was difficult for me, who made me cry.

Then I submitted the essay to many places: rejection, rejection, rejection… And eventually I submitted it to a contest. It was a finalist, and they said, “Your prize is that we will let you work with an editor, after which we will publish your essay.” And so for six months or a year, I went back and forth with the editor. During this, they said, “Some of these you don’t need. Some of these feel repetitive. Throw some of these out.” It originally was about twenty-five years of teaching, but now there are only twenty. They said, “This is about lessons your students have taught you. So you don’t have to go year by year. We’re just choosing the best.”

This conference is about teaching ideas, so I am very nervous that it won’t be the right fit. But I believe in it because this piece was published, and now I am going to share it. However, I am worried the stories of students will not translate well culturally.

Corr.: You, probably, have to say so much after so many years at community college system!

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Community college teaching is so challenging! There are students with mental illness, and they have troubled home lives. Many of our students are homeless – they just have a car, and they live in their car. And many of them are addicts. We have so much trouble with opioids. As a result, there can be so much drama in our students. Here is my strongest example. She is in this essay I am going to read in Minsk.

She is a student who was raised in a cage in the basement. She had been molested by her father. And there was her twin brother, too. One night her dad was drunk, and he unlocked them and killed her brother. The last thing she remembers is part of her brother’s brain lying on the floor. She climbed out a window and escaped. She even does not know how old she is. She thinks she was around eleven years old that night.

So she started living on the streets of Chicago when she was eleven. She would get on the L (short for “elevated”) train, the Metro, and she would just sleep on it. So, probably, it took two days before some drug runner saw her and thought, “Of course, this kid can run drugs for us!” It was a way for her to stay alive. She ended up with this drug culture in Chicago. She was very good at what she did, so she got involved with a Mexican cartel – with a drug family…

Years later, when she came into my classroom, she was probably in her early twenties. She had been a drug addict herself for a lot of years. She was getting clean from drug addiction. These women at drug rehab place taught her how to read. She came to me when she just learned to read a few months before! On the first day of class, I first talked to students. Then I said, “Now you have twenty minutes. You need to write me an introduction, and then you can give it to me, and then you are done today: bye-bye!”

After a while, the whole class leaves, and she is still writing. That was fine; I didn’t care. And finally I said, “I have another class. I have to go.” She came up with her piece of paper. She was shaking. She had about three words on it. She said, “I am telling you, I can do this class! I will be a good student for you, but I just couldn’t do it today. If you give me a chance, I will show you I can do this. I just need more time.” And I said, “OK. Let’s try it.”

She was the best student I have ever had. She took all of my classes including a Novels class. Towards the end of the course, we read a long novel. She finished it and sent me a message saying, “I’m crying right now because I never thought I’d be able to finish 724-page book.”

This story is so unbelievable that you have to know her to believe it because it sounds too cinematic. She is amazing, and she is still in my life.

Corr.: What is her name?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: She uses an adopted name that is not her real name. Basically, she got into this Mexican cartel drug life and decided get out because she was addicted. She was most likely born drug addicted, so she always had seizure disorder. When she was my student, it was during those years when I was having my babies. She had never seen a healthy pregnancy – she had only seen women on the streets who were pregnant. So she said, “Can I watch your belly grow?” When I had my son, she came to the hospital, and it was a very big deal for her.

She did not know how to swim, and she didn’t want to be someone who was scared of water. So I was like, “Sweetheart, let’s go to a swimming pool.” The first time we got to the swimming pool, she had a seizure. I had to pull her out of water. It was so scary and funny at the same time because I was holding her and hollering at the lifeguard who didn’t know what to do. I always joke that I’m kind of a child still, but as it turns out, I’m all right in a crisis.

We have a sport at our town which you also have in Belarus – biathlon, made up of skiing and shooting. She was good at running, so I said, “During warm months, we do a running/shooting biathlon. Let’s try this for you.” I took her there. She runs two kilometers and pop-pop-pop, runs two kilometers and pop-pop-pop! You should see her with a gun! She is amazing.

She came to our college, and she graduated from our college. Then she went to school to be an echocardiographer. She works in a hospital now. So she is one student who is in this essay I will read on Saturday in Minsk.

Corr.: Let us leave the States. How did you decide to try the Fulbright Program and come to Belarus?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: To be very honest, it was a little bit random. Most Fulbright scholars – 90% of them – have PhDs. So I had to be a little bit strategic. Most Fulbright scholars have to get a letter of invitation from a university. So you need to have an existing relationship somewhere in the world where you can ask, “Hey, guys, would you send me a letter of invitation?” And I did not have any existing relationship.

Thus, I was looking at the options of countries that wanted take someone with a master’s degree and that didn’t require a letter of invitation. Belarus was one of them, and in the description of what they were looking for was “teachers of English.” Even more, I was very interested to see post-Soviet culture. I saw the Eastern Bloc countries – East Germany and Czechoslovakia – in 1985. Then my sister was in Peace Corps in Moldova in 1998, and I stayed with her for three weeks there. We went to Romania, Hungary, and then in Poland. I thought, “Now another twenty years has passed.” I was very curious because Americans still have so many stereotypes! They still think all these states are so Soviet.

I am feeling very fortunate that my random choice of where to apply is proving to be such a rich experience. And it has only been maybe a month now. I cannot believe the hospitality here. I feel so well taken care of! And I feel so safe, which we do not have a lot in the United States in many places.

Corr.: Even in Minnesota?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I feel pretty safe in my city although there are of course some places that I avoid. A big problem in the States is guns. There is a whole business of, “We love our guns.” Well, half of the country does, and half does not. Every time I have a class, I genuinely worry about a student bringing a gun into the class. Have you seen all these shootings? In the last few years, college and universities shootings are happening more and more often, and our students have so much mental illness. A gun plus mental illness is exactly what creates this problem. I am genuinely scared. This is one reason why I appreciate online teaching more and more. In almost every class, there is someone where I think, “I’m pretty sure that there is a gun in that backpack” or “I’m pretty sure he has got a gun.” We have signs on our college doors saying “No guns allowed!” But there is no one checking.

Corr.: I just cannot imagine such signs at Polotsk State University!

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I live with this, and I still cannot believe it, to be honest. To me it is so unthinkable! How can this be?

But when I am here in Belarus, I feel so safe. No one has got a gun unless he is a policeman. The other thing I have really noticed is this: I have been doing fitness classes at the university. All these fitness classes are at night, which is unusual to me. Usually in the United States, it is like at lunch time or in the morning.

But then there’s Polotsk, 9 o’clock at night, and all these women are just leaving their classes and walking back home with no worries. In so many places in the Unites States, there is no way. You just would not walk alone after dark without a friend or without being really careful. So every night here I am walking home, and it is fine. Nobody is going to hurt me. Nobody is going to shoot me. And, you know, these concerns are very real in the States.

Also, I just love the pride Belarusians have in their nationality and their country. It has been a revelation. Here is one thing that brings me pleasure: I love these local wooden houses. And I keep posting pictures of them because Americans cannot believe it, either. They are so colorful! They are so charming – yellow and red… I did not expect this! It is so great to be here and to see this reality. Americans have no idea about Belarus. Everyone keeps asking me “How’s Russia?” And it is so annoying. I am like, “I don’t know. How’s Canada?” Belarus and Russia are as different as the USA and Canada. The distinction is important.

I am not with my husband and kids, and I thought that I would just be sad and lonely. But I am having a really good time.

Corr.: So to make this trip to Belarus possible you decided on a temporary separation from your loved ones. Please tell us about your family.

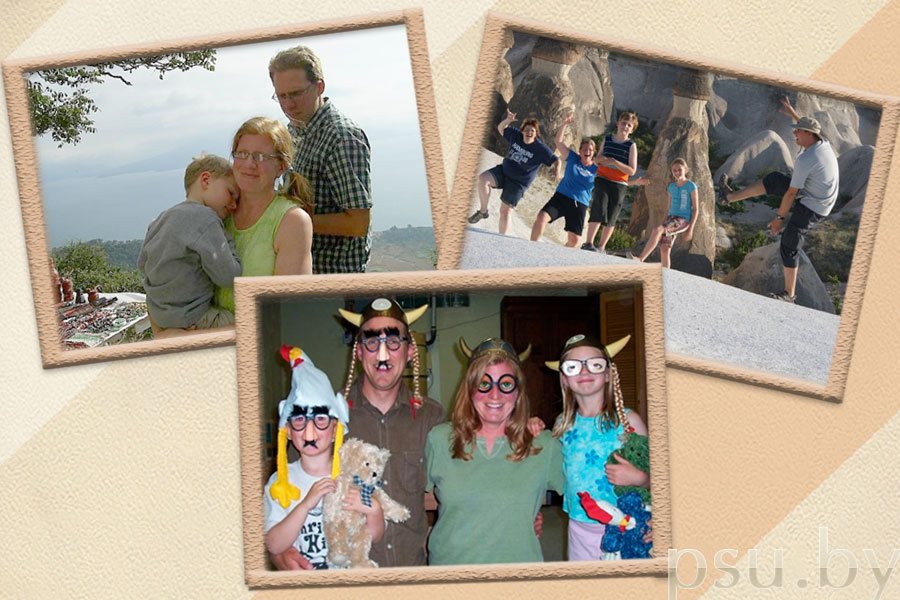

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I met my husband in 1999 when my cousin decided to set us up on a blind date. Very quickly after that first meeting, we knew we wanted to get married, and after the wedding some months later, he moved to the town where I was living and teaching at the community college. In short order, we had our first child, our daughter who is now 18 and in her first semester of college. When we started our family, we had to decide what we wanted to do about childcare, and we decided we wanted to have a parent who stayed at home. As we weighed that decision, we considered that my salary was two times better than his. He had been an administrator at an environmental education center in Northern Minnesota. His job would be from 8am to 5pm whereas my classes would be, say, on Tuesdays and Thursdays. So we decided that I would work, and he would stay home with our kids. He was a stay-at-home parent for 14 years, from the time we had our daughter, through when we had our son, all the way until they were in school. Staying home and dealing with the household suited his temperament. It gave us a really good life because when we want to take trips, I had my summers off, and he did not have a job. So we would just go! We have been married for 19 years and, I think, I have made dinners three times. He cooks. He is just amazing. He does everything, and he is very gentle and mild. And he has no resentment. I would have resentment if I had stayed at home. I would think, “I’m an intelligent person… This is boring… And kids… I’m always doing the work, and you go off and have time away…” But he always says, “It’s good… It’s good… It’s good…”

He brought this same attitude of acceptance to my Fulbright experience here in Belarus, realizing that it is a huge opportunity for me, yet it isn’t a good time for the family to accompany me due to our son’s need to continue with his academics at his high school. So right now, as I have these months in Belarus, our daughter is having her own adventure as she starts college while my husband and son stay at home and “hold down the fort,” as we say. All of this is possible for me because of my husband.

Corr.: So you are happy!

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Yes, he is so perfect! He is my favorite person. He has now transitioned back into the workforce. Now, he is the Director of Circulation at the public library in Duluth where we live. He is very happy with the work he is doing. He works with books and people, and I work with people – my students – and books.

Corr.: That is real harmony! Let us return to your Fulbright fellowship. What do you think about our university, our humanities faculty, and your students?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: I have been here for only one month. The thing that has been most interesting to me, to be honest, is how all the English teachers – I have mostly met English teachers – are women. It is so unusual to me. In classes, it is the same with the English students! I have to keep asking, “So, would you explain to me, where are the boys?”

I am wondering: what are the reasons for this? Maybe this job is lower paying. There can be many reasons. In my English Department at my college in the States, we have male faculty. In our classes with our English major students, there would be just as many males as females. For me, that has been something I really notice.

Whenever I report to my friends and family in America, I am always talking about women. You know, so far I have just met two men at the university. You are #3! For me, this lack of men in my days is so different. And in the fitness classes, there are all women. In the States for our fitness classes, I am always with men, too. But here, I have realized that I do not have any men around. As a result, I cannot talk about Belarusian men. But I can really talk about Belarusian women.

Indeed, the colleagues I have met here are pretty much women. And I cannot believe how much they work! I look at Vera Hembitskaya… She has been very helpful to me because she did Fulbright, and she is in Polotsk. She teaches so much! The teaching days here are so heavy and long compared to what I am used to. But these teachers are so committed and good natured about it. After the first day of class I said, “Oh, Vera, you must be exhausted! How you are doing?” And she replied, “It was such a good day! I just really like these groups of students! I wasn’t tired at all!” And I was thinking, “Wow! That is impressive.” Sometimes I teach one class, and I am ready for bed. So I feel there is great energy and genuine dedication among these colleagues that I have seen.

And I have never felt so appreciated. People here make me feel like they want me in the room. I am not always used to that. In America, my students frequently do not want me in the room because they, themselves, don’t want to be in the room. But here there is this feeling that everyone really would like to interact with a native English speaker. I feel so valuable here. My colleagues are very good at making me feel valuable. I realize that I do not always have that in the States.

And the same feeling comes from the students because the students here are very respectful, and focused, and diligent. I am not always used to respectful students.

Corr.: Community college?

Jocelyn Pihlaja: Yes, community college. Some semesters, with some classes, it feels like chaos. There was one moment a few years ago – the toughest class I have ever had. I was explaining thesis statements – the controlling idea of an essay – and how to create a strong thesis statement. I was going through the criteria for a good thesis statement, and I was in the middle of the sentence about, “… at the end of the introduction you have to need this controlling idea...”

All of a sudden, a hand shoots up, and I think, “Yes!” This student is clicking on her computer and beckoning me over with her finger. Then she says, “I’m trying to get a car insurance quote. Could you… Do you know a good website ‘cause I have to have it by the end of the day?” It was breathtaking… Anyhow, the students coming to the class here are like magic. It is fantastic! Maybe I am particularly lucky with the groups that I have.

The other thing that I have been surprised about with the Belarusian students is I hear from teachers and from Fulbright colleagues at other places that their students are so quiet and never talk. And I have been very surprised because these students at PSU talk very easily. Perhaps part of it is that I do not speak Russian. There is no another way to communicate; they have to use English. But I also think they realize in a certain way I do need help. Sometimes I just need to say to them thing like, “I was trying to find socks. Where would I go to buy a pair of socks?” and they talk to me because I am helpless unless they are willing to give me information. Therefore, I think they are more willing to speak with me.

It is almost good that I do not have Russian. My younger Fulbright colleagues in other Belarusian cities right now all have at least two years of Russian, if not more. And actually they are speaking quite good Russian. But sometimes they say, “I cannot get my students to talk! I am doing a conversation club, and it’s always just me talking, and they just stare at me, and they will not talk.” In contrast, I am like, “Wow, my students are always talking.” I am very impressed that the students – even if they are not feeling perfect with their language – are willing to talk and make the mistakes. That is the only way to learn a language – you have to just try it! And it is good to make mistakes. That is the part of the process.

For sure, I am in love with the students. There is an innocence in the students here that is so lovely. They seem younger than American students. And I do mean this as a compliment! Here, an 18-year-old seems really like an 18-year-old and not 28. Many times, my community college 18-year-old students already have two children and are divorced. So it is really nice to see that there is something fresh and innocent here.

For example, last Friday, I went to one of the gymnasiums in Polotsk. I get so nervous to speak in front of people, but I went into the auditorium; it was like a theater – students, and students, and students! They all had questions prepared for me like, “What is your favorite kind of movie?” At the end they all came up and wanted almost to hug. They were so sweet! This is a delight to see some sweetness in the world in young people. It is reviving my heart.

So I am very impressed with the colleagues and with the students. There is something earnest and genuine. It is such a good energy. Of course, it has been only a few weeks here, so I have not seen a lot of reality. I know there is always reality, but for now I am going to enjoy this professional honeymoon period!

Interviewer: Vladimir Filipenko

Photos: family archive, Polina Kosarevskaya, Irina Shipko

We would like to thank Elena Potapova, senior lecturer at the Department of World Literature and Foreign Languages, for her assistance in organizing and conducting the interview and for preparing the text for publication.